Essentially all of my work involves reading and writing. I write papers and proposals, code, documentation, emails, and I jot down thoughts in problem-solving sessions. And all of that is in relation to the writings and ideas of an incredibly large number of people.

Keeping up with all this information requires knowledge management systems. They are often integrated into our online experiences - we have bookmarks, searchable email inboxes, online code repositories, etc.

But some effort is needed to use these systems effectively, without being overwhelmed by all of these disparate systems. That’s where personal knowledge management comes in.

It’s not a new idea. For millennia, beginning at least with Aristotle, writers have been using “commonplace“ books to organize their notes, quotes, and ideas. Stephen Johnson, in the book Where Good Ideas Come From, relates Darwin’s notebooks to this tradition:

Darwin’s notebooks lie at the tail end of a long and fruitful tradition that peaked in Enlightenment-era Europe, particularly in England: the practice of maintaining a ‘commonplace’ book. Scholars, amateur scientists, aspiring men of letters - just about anyone with intellectual ambition in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was likely to keep a commonplace book. The great minds of the period - Milton, Bacon, Locke - were zealous believers in the memory-enhancing powers of the commonplace book.

Something as simple as the “notes” app on your phone, or sending yourself emails, can work well enough for note-taking. But we can get much more out of our notes by using technology to help index notes, create connections between them, and help summarize and extract relevant information when needed.

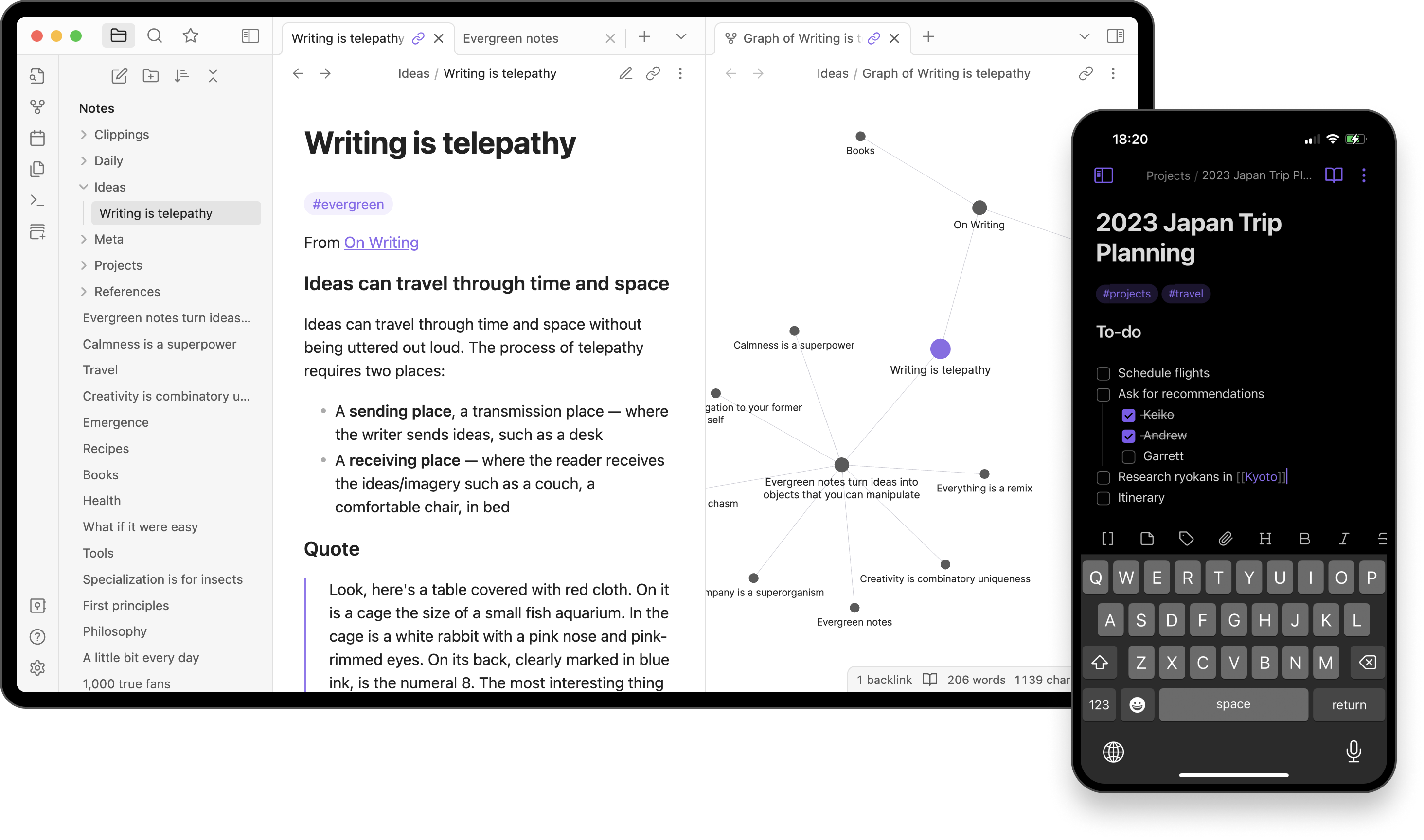

Technology can also help us overcome the challenges of determining how to organize notes. Personally, I cannot keep any file tree well organized. There is an alternative: instead of a hierarchical tree, we can organize notes in a graph using tags and links. This is how Wikipedia is structured. You don’t find a wiki page by going down a file tree. Rather, you do keyword searches and follow links between pages.

My favorite tool for this is Obsidian (at work I use Confluence). Previously I used Notion, and before that I only used paper. Obsidian is free, easy-to-use, private (it’s a desktop app!), and responsive. I use it to keep track of everything that isn’t my paper notepad, emails, or LaTeX/Word documents.

There are lots of other tools available:

In short, it’s easy to take modern digital features like hypertext or search for granted. But it’s really amazing how far we’ve come to get here, and I think we can do even more amazing things if we can use these features to their full extent or push them even further.