The Pareto principle, or the 80/20 rule, states that 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes.

Surprisingly enough, this principle has general statistical underpinnings and does actually occur in a broad range of situations. The numbers 80/20 could be something else, but there is often an imbalance of this sort. It’s related to selection bias and size bias. Let me explain in the context of software development.

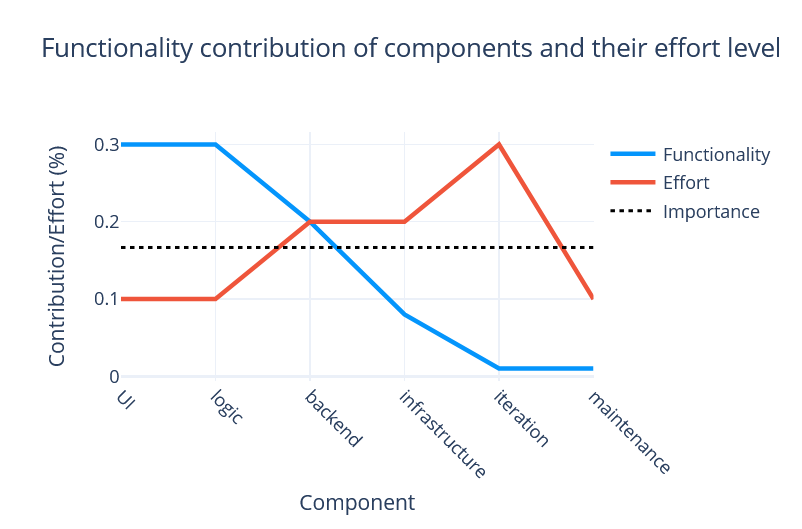

Say you’re building a piece of software for some use case. There’s a lot that goes into building and deploying the software: the UI, the logic, the backend, the deployment infrastructure, the iterative changes, etc. Each part contributes more or less to the functionality a user can see.

In this plot, UI+logic+backend is 80% of the functionality* the user can see, but only 40% of the required effort to complete the project.

If functionality and effort are uncorrelated or negatively correlated, then building the most functionality first will lead to decreasing return of efforts on functionality over the project’s life. The smallest set of components that contribute to 80% functionality is a biased selection that isn’t representative of the overall effort distribution.

This doesn’t mean that the 80% seen functionality is more important than the other 20%. In fact, your software is going to be useless if you can’t build the infrastructure it needs for deployment. All components are equally important in this example. This mismatch between true value and apparent functionality can be dangerously misleading.

Why Software Projects Fail

The Pareto principle plays into the common failure (or cost overrun, scope creep, technical debt) of software projects.

Often, development teams prioritize building a minimal viable product (MVP), or delivering the most apparent functionality for a given effort level. The fast achievement of 80% functionality can lead to poor expectations of what’s needed to reach a product that has actual value, i.e. something maintainable and deployable. Clients, project managers, and developers can misunderstand the scope of project if they rank tasks in functionality-first order, without considering the full value chain.

A Better Approach - Managing Risks And the Full Value Chain

As part of good project management, you want to:

- Map risks and uncertainties, and address the most important ones first.

- Deliver self-contained value to the client throughout the project, if possible.

E.g. for (1), if you don’t know what a client wants, that’s a big risk. Getting an MVP in front of them might help reduce uncertainties and mitigate that risk. A cost overrun is also a big risk. If you don’t know how long it will take to build the infrastructure to deploy your system, then you might want to address that first.

For (2), note that value is not always the same as functionality. Undeployed functionality has no value to a client. An MVP, unless it is truly viable on its own, typically has little value to a client. A product that doesn’t meet quality requirements does not have any value. If clients hire you for software development, value is something they can use without any further software development.

In Short

The Pareto principle is both about the big impact you can have from a few actions (e.g., achieve 80% in 20% of the time), and how easily misled you can be about scope and impact (e.g., forgetting about a necessary 20% that takes 80% of the time).