Everything that follows is a quote from Terry’s book, with minimal adaptations for flow in some places. It’s an excellent book. Get it here.

The most potent opportunities seldom show up labeled as “projects,” but arrive disguised as problems, issues, or murky messes. Tackling so called Big, Hairy, Audacious Goals, as Jim Collins describes them in Built to Last, involves juggling a full spectrum of slippery Objectives that can be difficult to define, let alone manage.

In the pages ahead, I’ll walk you through a flexible thinking process, and show you how to sort through the fog of fuzzy ideas and develop sound strategies and executable plans. You’ll see how these tools scale up and down to handle issues of any size and flex to fit multiple situations you may face. But first, let’s review why most project plans are inadequate. See how many of these resonate with your personal experience:

| Planning Mistake | Solution Elements | | |

Tolerating Vague Objectives In the rush to implement, not enough serious, upfront thinking goes into clarifying Objectives, Measures, and their interconnections. |

|

Ignoring Environmental Context Projects unfold in unpredictable ways, but people sometimes think myopically and ignore how risk factors outside their project boundaries might affect them. |

|

Poor Planning Tools and Processes When the only tool is a hammer, the whole world looks like a nail. Before firing up your PC, fire up your brain and flesh out your project strategy. |

|

Neglecting Stakeholder Interests Projects are real-life dramas played out by multiple actors who bring their own agenda and varying degrees of interest and support. |

|

One-shot Planning Like home-baked bread that grows moldy with time, project plans have a limited shelf-life. They must be updated to reflect new learning and progress. |

|

Mismanaging People Dynamics Project success requires the committed, coordinated action of many people. |

|

The Four Critical Questions

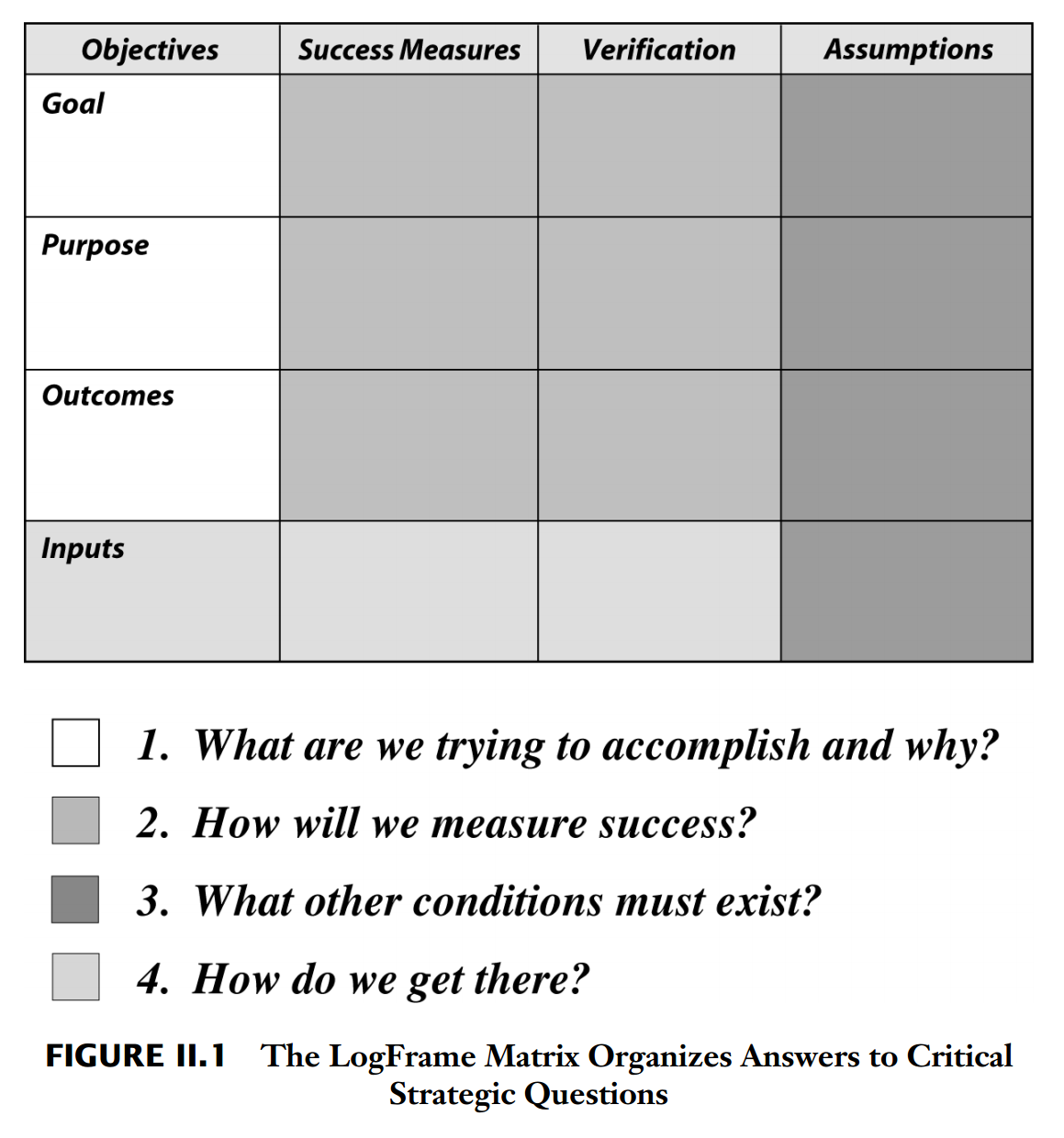

All great solutions begin by asking the right questions. They seem like simple questions - that’s exactly the point. They are indeed simple, but not simplistic. The four following carefully crafted questions work wonders in virtually any situation. The first three are usually glossed over in the rush to answer the fourth.

What are we trying to accomplish and why?

The question of what the project should accomplish - and more importantly - why it needs to be done, deserves fine-tuned attention because those answers drive everything else. In the rush to decide on the how, who, and when of a project, people often gloss over the why.

How will we measure success?

This question is significant because Measures flesh out and anchor what the Objectives really mean. Until you define how success will be measured, even the most sincere visions are no more than highfalutin’ fluff.

What other conditions must exist?

This third question puts your project, issue, or initiative into a larger strategic context. Asking this expands the analysis to include some of the outside factors which may disrupt your carefully crafted plans.

How do we get there?

The majority of project teams I have worked with tend to delve deep into the details much too soon, or get sidelined by premature technical arguments. They gloss over the first three questions in a rush to get moving. The value of the fourth question comes from consciously placing it in its only, truly functional place in the planning sequence: Last.

LogFrames

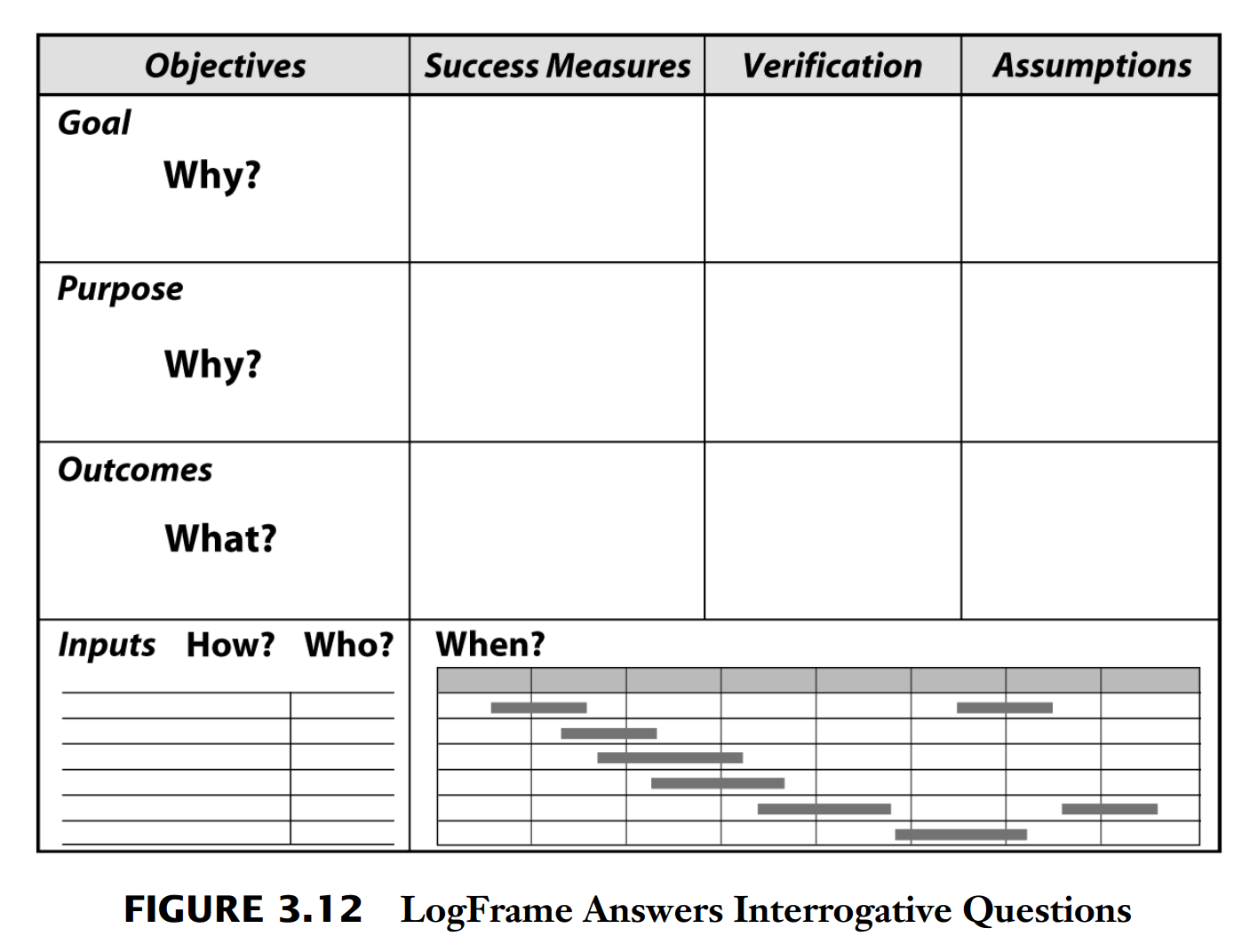

While the LogFrame matrix may initially seem intimidating, the ideas it captures are basic. The four strategic questions offer a user friendly way to learn and apply this tool. These questions are inherently embedded in the matrix and answering them helps you design your project in a way that connect all the dots.

What Are We Trying To Accomplish And Why? (Objectives)

The first column describes Objectives and the If-Then logic linking them together. The LogFrame makes important distinctions among various “levels” of Objectives: Strategic intention (Goal), project impact (Purpose), project deliverables (Outcomes), and the key action steps (Inputs).How Will We Measure Success? (Measures and Verifications)

The second column identifies the Measures of sucess for Objectives at each level. here wew select appropriate Measures and choose quantity, quality, and time indicators to clarify what each Objective means.

The third column summarizes how we will verify the status of the Measures at eaech level. Think of the Verification column as the project’s management information and feedback system.

What Other Conditions Must Exist? (Assumptions)

The fourth column captures Assumptions; those ever-present, but often neglected risk factors outside of the project, on which project success depends. Defining and testing Assumptions lets you spot potential problems and deal with them in advance.How do we get There? (Inputs)

The bottom row captures the project action plan: Who does what, when, and with what resources. Conventional project management like Work Breakdown Structures (WBS) and Gantt chart schedules fit here.

LogFrame Tips

Treat the matrix as a summary. Keep it clear and concise; supplement with other documents.

Make sure everyone on the team has working understanding of the LogFrame (at a minimum, knowing the four critical questions).

Make sure the right peopole are involved. Invite key stakeholders to participate in project planning.

Stress the importance of the process of planning as much as the plan that comes out of the planning process. Supplement liberally with other supporting tools.

Iterate to make it great. Consider the first Logframe to be a rough draft that will require revision and reworking, perhaps through many cycles.

Build in specific milestones on the calendar at which you refine and revise the matrix in the light of new information.

Monitor and manage changing Assumptions over time.

Turning a Problem Into a Set of Objectives

A problem is simply a project in disguise. Projects masquerading as problems must first be converted into Objectives before advancing to solutions. Spend some time carefully diagnosing the problem because the way you define it shapes the range of solution options. Don’t get sucked in by an over-simplified definition, catch phrase, or symptom. Get at the root causes. Find the right problem to solve.

Stakeholder collaboration during problem analysis builds shared understanding, generates better solution approaches, and greases the skids for smoother execution.

Ask Your Stakeholders

What do you see as the problem?

Why is this a problem and for whom?

What causes the problem?

What are the consequences if we ignore the problem?

How will you know when the problem is gone?

What benefits will a solution bring?

What might an ideal solution look like?

Exploring Distinctions Among LogFrame Levels

Goal: The Big Picture Impact

The Goal is the big picture context — the overarching corporate or strategic Objective to which your project, and usually other projects, contribute.

Some typical Goal examples:

Delight our customers

Become the top provider in the market

Increase corporate profits

Ensure reliability of the nuclear stockpile

Foster a climate of innovation

Be the global leader in safety education

These secondary trigger questions can help you get to the priamary Goal of a project:

What is the higher corporate or strategic Objective to which this project contributes?

Why is the project’s impact important?

What should happen after we achieve the Purpose?

What is the big picture reason for doing this project?

Purpose: The Project Sweet Spot

Purpose is the vital, often missing focus that expresses the desired result or the impact we expect the project deliverables to produce. It describes expected change in system behavior, whether the system of interest is a core process, a new organization unit, or target customers. Purpose floats a level above that which we can directly control — the Outcomes. It’s a subtle concept, often hard to grasp because we are so conditioned to thinking of activities and Outcomes.

Consider these examples:

| Outcomes Statement | Corresponding Purposes |

|---|---|

| System built or delivered | Customers use our system |

| Process improved | Improved process used |

| System developed | System successfully implemented |

| Staff trained in safe procedures | Staff operates machinery safely |

Here are some trigger questions you can ask to articulate the Purpose:

Why are we really doing this project?

What would the clients or users like to see happen because of this project?

If this project were a success, how would we know?

What impact are we trying to achieve?

Outcomes: What the Project Will Deliver

Project Outcomes describe what the team can, must, and commits to make happen to achieve Purpose. They can be functioning systems or processes (i.e., recruiting process operating) as well as completed end products (i.e., prototype built) and delivered services (i.e., people trained). They describe the specifi c end-results (or deliverables) expected from implementing a series of activities or tasks.

Use these questions to help solidify required Outcomes:

What are our main project deliverables?

What do we need to make happen in order to achieve the project Purpose?

What are the end results for which the project team can be held accountable?

What processes do we need to put in place to achieve Purpose?

| Inputs (Activities) | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Train users | Users trained |

| Improve skills | Skills improvevd |

| Determine best methods | Best methods determined |

| Build new office | New office built |

Four Tips for Meaningful Measures

Don’t fall into the trap of measuring only that which is easy to measure. Measuring Inputs and Outcomes is most straightforward, but progress towards Purpose and Goal is what really counts. The best Measures meet these criteria:

Valid — They accurately measure the Objective. Changes in the status of Measures accurately reflect changes in the status of the Objective.

Verifiable — Clear, non-subjective evidence exists or can be obtained. This third LogFrame column

identifies processes and mechanisms for determining the status of Measures in column two.Targeted — Quality, quantity, and time targets are pinned down. Choose targets that are sufficient to achieve impact at the next higher level. Sometimes, rather than locking in a single number, it’s appropriate to state a rough range.

Independent — Each level in the hierarchy has separate Measures.

Goal Measures tend to be broad macro-Measures that include the long-term impact of one project or multiple projects aimed at the same Goal.

Purpose Measures describe those conditions we expect will exist when we are willing to call the project a success.

Outcome Measures describe specific tangible results that the project team can make happen and commits to doing so. Describe them as completed results (using the past tense verb form, such as “System developed”or “Training completed”).

Input Measures deal with activity, budget, and schedule.

Purpose Measures are the most important in the hierarchy. Why? Because that’s your primary aiming point, the what-should-occur result you expect after you deliver what you can.

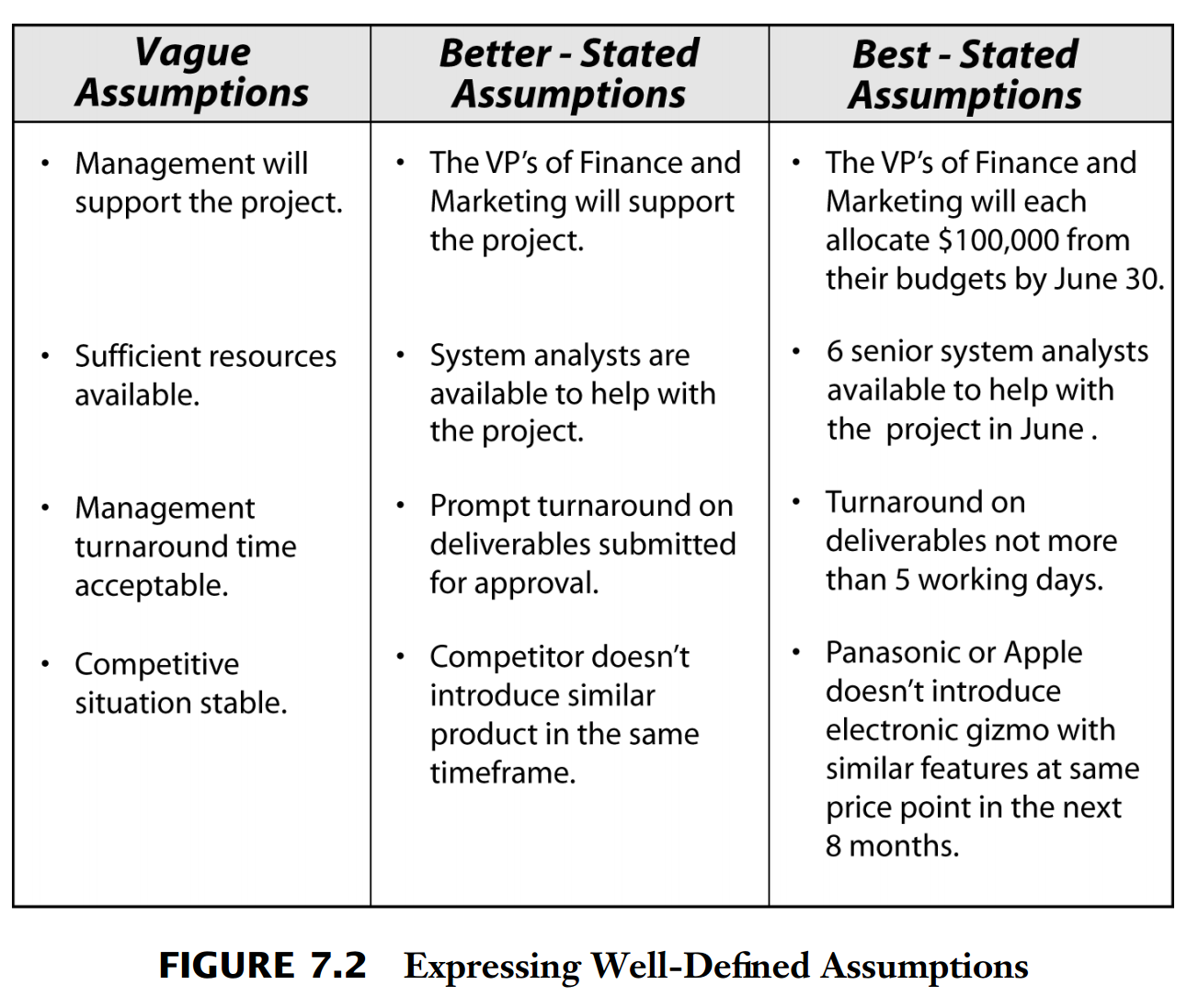

Three Steps for Managing Assumptions

Step 1. Identify Key Assumptions

Brainstorm all the conditions you believe are necessary to go from one LogFrame level to the next.

Step 2. Analyze and Test Them

Try to assess the degree of risk you can expect from these critical Assumptions by using a simple rating system or probability percentages. Decide which Assumptions to highlight in the LogFrame matrix.

How important is this Assumption to project success or failure?

How valid or probable is this Assumption? What are the odds that it is valid (or not)? Can we express it as a percentage? How do we know?

If the Assumptions fail, what is the effect on the project? Does a failed Assumption diminish accomplishment? Delay it? Destroy it?

What could cause this Assumption not to be valid? ”(Note: This one raises specific risk factors.)

Step 3. Act on Them

Put each key Assumption under your mental microscope and consider the following:

Is this a reasonable risk to take?

To what extent is it amenable to control? Can we manage it? Influence and nudge it? Or only monitor it

What are some ways we can influence the Assumption?

What contingency plans might we put in place just in case the Assumption proves wrong?

How can we design the project to minimize the impact of, or work around, the Assumption?

Is this Assumption under someone else’s control?

How could we design the project to make this Assumption moot or irrelevant?

Aligning Projects With Strategic Intent

The LogFrame can be the cornerstone of any unit-level management system. However, this presumes that there is a sound, overarching strategy to begin with.

Strategy is the particular means chosen to get from where you are to where you want to go, selected from multiple possibilities and reflecting your vision, mission, and values. An overall Strategy (big “S”) usually consists of multiple strategic initiatives (small “s”), which are executed through programs, projects, and tasks.

Strategic planning steps:

Clarify the Planning Context and Issues - Be clear about your expected planning Outcomes and identify issues to include.

Involve Key Players - Decide who to involve in your process to build buy-in and stay-ini.

Scan Your Environment - Identify what’s changing in your environment; and analyze divvision and department plans to extract Goals your group shares or owns.

Revisit Your Vision/Mission/Values - Turn these “fluff“ statements into high-performance tools that energize staff and build shared commitment.

Sharpen Your Goals and Measures - Develop a meaningful performance scorecard that identifies how you deliver customer value.

Develop Core Strategies - Turn Goals into strategies, and test those strategies for impact against Measures to ensure smart choices.

Turn Strategies into Executable Plans - Using the Logical Framework. Let the responsible players flesh out implementation plans.

Follow Up and Continue the Process - Build momentum by revieweing and updating the plans while strenghtening the planning process itself.

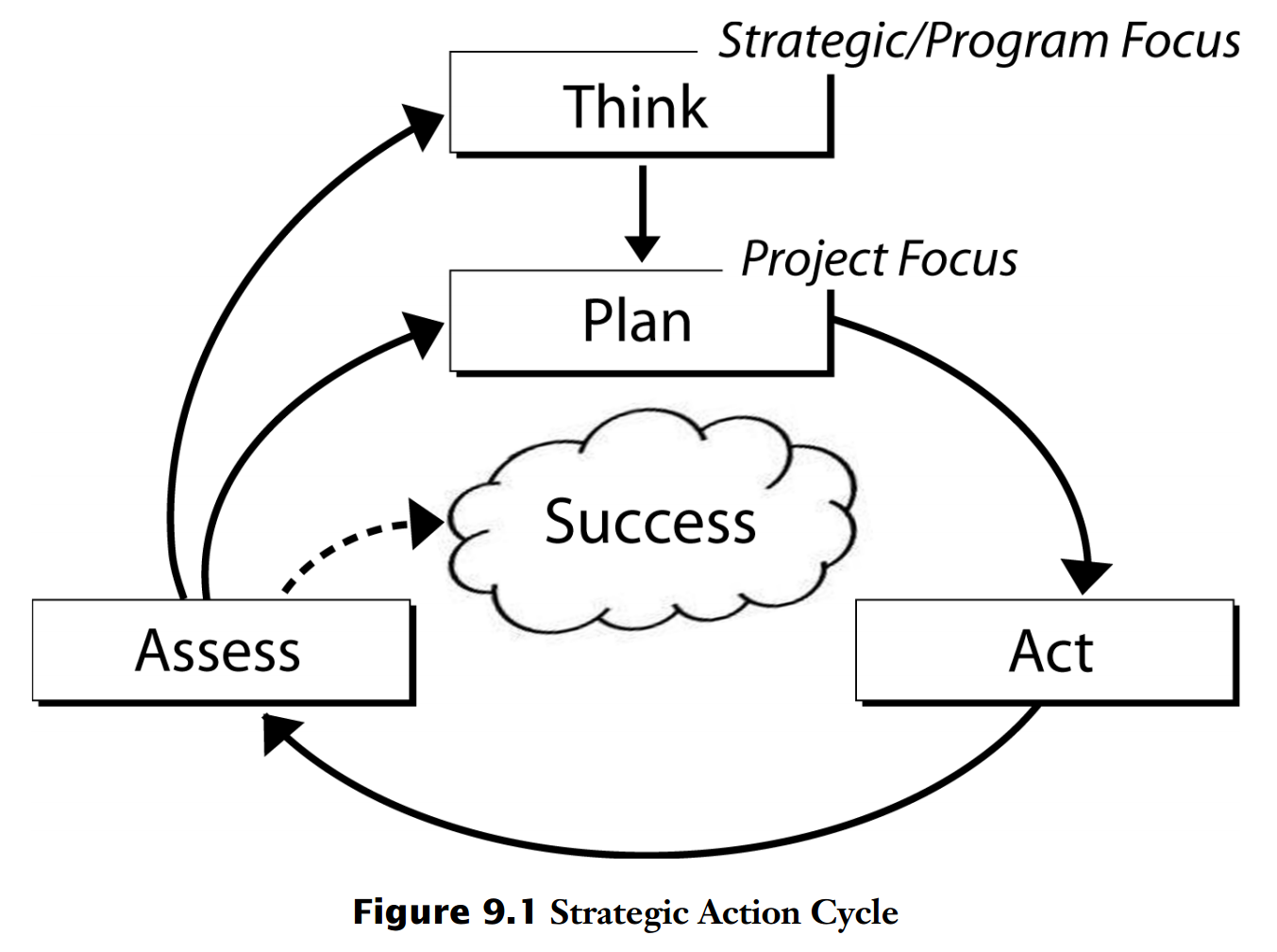

The Strategic Action Cycle

The cycle begins with “Think,” the big picture strategic/program focus which follows the process from Chapter 4, or an equivalent strategic planning process.

Results of strategic thinking identify projects to be managed with the Plan-Act-Assess cycle.

Project plans created with LogFrames provide a solid foundation for action (execution/implementation) and Assessment.

The Assess block can complete the loop in three ways. If assessment shows that success has been achieved - as defined by project Purpose - the project can be considered complete.

Project Monitoring is an ongoing process of tracking budget and schedule against deliverables and making tactical adjustments. It presumes the Logical Framework is the best design and focuses team attention on translating Inputs into Outcomes.

Project Review is an occasional process that asks managers to step back from the day-to-day work and reassess their approach. It challenges the project design and invites changes in the LogFrame, with emphasis on the Outcome to Purpose link.

Project Evaluation examines impact and cost effectiveness. Project evaluations are often timed as the end of one phase nears and another is about to begin, or after the project is over. Evaluation examines Purpose to Goal linkages.

Other

The process of planning is more crucial than the planning documents that emerge at the other end. The collaborative use of the LogFrame helps you simultaneously build and shape a strong team while they work together to create an actionable plan.

Make sure that everyone speaks the same language by agreeing on what your key terms mean and using them in a consistent way.

The LogFrame matrix usually shows four levels, but Objectives above the Goal can be included to illustrate a higher level of impact. The higher up the hierarchy we climb, the more long-term, general, and “vision-sounding” these Objectives become.

Don’t ask “Hows it going on this task?“ Instead, ask:

Are you having difficulties that would keep you from meeting targets?

Are you getting the support you need from others?

Is there anything else I should know about this?

What do you need from me?

Project monitoring asks “Are we on track?“; project reviews ask “Are we on the right track?“ Use the LogFrame to challenge your strategy by posing questions such as:

Is our Purpose still valid? What’s our progress toward Purpose?

Is our Purpose likely to be achieved with this plan? Will this Purpose get us to the Goal?

What is the status of Assumptions?

Are these the right Outcomes? Are we producing them effectively?

Should new Outcomes or Assumptions be added? Existing ones dropped?

How should we rervise our key strategic hypotheses (Outcome to Purpose to Goal) to produce better results?

Because the LogFrame’s systems thinking underpinnings are generic and flexible, so is the grid format itself. Be innovative and customize the LogFrame to your needs and add your own categories.

At times you’ll need to zoom in on a project component for more visibility. Some tasks are large enough to justify their own LogFrame.

Make responsibilities clear to all

Clarify Resource Requirements

Analyze stakeholder interests

Manage with emotional intelligence